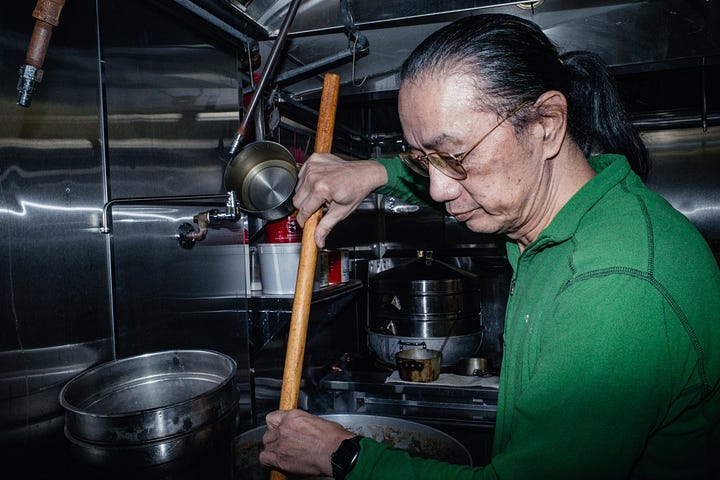

“A Chinese food kitchen is like hell,” is what Stephen Li tells me, as his dining room swells during a dinner rush. He’s just taken me into the kitchen to see an enormous cauldron of broth; as he stirs it, a thick vapor of poached shrimp and roasted fish wafts over me. It’s one of four pots that he’ll go through today. We move back into the dining room to share a glass of wine.

This is Great NY Noodletown. Opened in 1964 by Tina and Timmy Moy, it has served as a reliable, old-school Cantonese spot as beloved for its BBQ and wontons as it was for its 4 AM curfew (since the pandemic, Noodletown now closes at 11 PM). Stephen began managing the joint about 30 years ago, after globalization caused his garment business on Lafayette to crumble in the 1990s.

“This is the real Chinese food style,” Stephen says, as we devour plates of roast pork and duck. “Especially the Cantonese. We specialize in making fresh food.” The soft shell crabs, for example, are only available seasonally (the season is now). The BBQ guys work all day, sliding whole pigs through the air into enormous ovens, suspended by hooks. And the wontons are made in the basement each morning.

Stephen is 74 years old, and favors track suits. His pony tail, he tells me, has gotten him recognized in airports. I covered more of his story on video here.

But besides being a Chinatown landmark, Great NY Noodletown is also one of New York’s most beloved BYOB restaurants. I love drinking wine, but I can’t afford to drink much of it in restaurants. So I’ve asked one of New York’s most prominent wine importers, and author of the Substack Wine Wine Wine to contribute a column to People & Food about what wines to bring to these spots. Please give a warm welcome to Steven Graf:

Somewhere on the wine route, food pairing really fell out of fashion. Professionals wanted to demystify wine, to make drinking less pretentious and more quotidian.

Their argument was that a good bottle is good at any time, under almost any circumstance, and no stuffy, pinned sommelier has a right to say different. Wine is for anyone, anywhere, whenever they want it. And while I broadly agree with this sentiment, I do sense a small loss in one of the great culinary romances of food and wine.

Therefore, in this series on New York’s beloved BYOB restaurants, we are going to delicately reopen an old book and talk a little bit about the art and science (and party trick) of wine pairings. Here’s what we brought to Great NY Noodletown and why.

May it guide your next visit with intrigue, confidence and zeal.

The Challenge of Pairing Chinese Food with Wine

Typically, when I’m choosing a wine for a meal, I look to tradition and see what our grandparents or great-great-great grandparents liked to eat with a certain dish. In Europe and other wine-producing regions, the pairing is usually straightforward and easy to search. Boeuf Bourguignon tells you what to drink in its name, but not so for duck wonton soup and salt and chile soft shell crab.

But this lack of tradition can offer advantages. What I tend to do is break these dishes down in terms of acid, salt, fattiness, spice, etc., and find wines that bring about flavors greater than the sum of their parts.

The menu at Noodletown is full of fatty dishes, spicier than most European cuisines, very salty, and loaded with umami. There are some dishes that juxtapose sweet and savory, and all-in-all, an enormous amount of depth and complexity. A trained sommelier will often sell you a bottle of German Riesling in these circumstances (or something like it). The logic is that Riesling’s high level of acidity will cut through the fat, giving dishes structure. Additionally, he or she will suggest a bottle with a touch of sugar such that the sweetness can counter the spice. It’s become a textbook pairing.

While I’ve had some nice experiences with off-dry Riesling in these situations, there are some problems. For starters, not all “acid” is the same. While there are many types of acid in wine, two are the most relevant here: malic acid and lactic acid. Malic acid is snappy, bright and prominent in fruit like green apples.. Lactic acid (lactose) is softer and less piqued. It is found in milk and cheese.

The “High Acid Wines” like Riesling, Muscadet, or Grüner Veltiner are all high in malic acid.. Malic acid serves its purpose by lending structure to a fatty dish, but for me, high amounts of malic acid can linger in your mouth the way tannins do. When you’re eating food with even a moderate amount of spice, I find both malic acid and tannins hold spice in your palate in an uncomfortable way. So that’s a problem.

Very often, the intuition with pairing in general is to fight fire with fire: Big bold spices = opulent, rich, fruit. But slightly sweet wines may also find themselves at odds with dishes that have their own touch of sugar, where the combinations become cloying and the dish loses its backbone. These pairings can work, but often I find them cacophonous and a disservice to the food and the wine. Even in the best cases, sweetness will neutralize spice, which is not exactly the goal.

With all of that in mind, here are the pairings we came up with.

Dish #1: Duck Soup Hor Fun + Les Aricoques, Rousette de Savoie ($69.99, Wine Searcher Link)

This dish is made with a traditional, Cantonese, 3-hour broth of poultry and seafood that perfectly distills all the flavors and ingredients of this kitchen. The spice is mild but broad — sort of humming in the background. The fat is sweet from shrimp heads and crab shells. Duck and chicken bones give that perfectly glistening sheen of richness where all the salt seems to be couched. How does a wine compete with the nest of chewy noodles that soak up the soul of this place for each and every glutinous bite?

A cursory search for traditional pairings offered the key. Amongst many rice and fruit distillates, fermented milk popped up a handful of times in the available literature (read: Reddit threads). How does one find sufficient acid to cut through a symphony of animal fats while avoiding too much sharpness? How do you get something soft and round without sugar or flabbiness? Lactic acid was apparently one historical answer that I’d try here.

Rousette (or Altesse) is a naturally low acid variety from Savoie. In this wine, malolactic fermentation was not blocked. The result was a wine with almost no bite, but plenty of mild tartness — the kind you find in yogurt. It was unctuous with a hard “c.” — Just enough to clean the mouth while also lending a note of mild, alpine cheesiness that fits so perfectly here. Rousette also lends an almond nuttiness. It gives something sweet without disrupting the PH of the dish or getting in the way of that subtle spice. Alternatives might include the dreaded buttery Chardonnay (within reason. Subtle, understated versions abound in Burgundy and California). Southern French varieties like Marsanne or Viognier will also do the trick, but with more tropical fruitiness and weight.

Dish #2 Roast Duck + Monastero Suore Cistercensi, Lazio Rosso 'Benedic' ($32.99, Wine Searcher link)

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to People & Food to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.